MOTHERS’ & FATHERS’ TIME WITH CHILDREN

OBJECTIVE ASSESSMENTS: TIME DIARIES

Mothers’ time with children has overall, remained surprisingly high across recent decades, measured from time diaries in 1965 through the present. Despite the fact that mothers, even those with young children, marched into the labor force in unprecedented numbers in the latter part of the 20th century, mothers’ time spent in childcare as a primary activity actually increased. Mothers’ “total contact time” with children is about the same — for married mothers, it increased slightly (but not significantly) and for single mothers, it decreased slightly (but not significantly).

Mothers’ time with children has overall, remained surprisingly high across recent decades, measured from time diaries in 1965 through the present. Despite the fact that mothers, even those with young children, marched into the labor force in unprecedented numbers in the latter part of the 20th century, mothers’ time spent in childcare as a primary activity actually increased. Mothers’ “total contact time” with children is about the same — for married mothers, it increased slightly (but not significantly) and for single mothers, it decreased slightly (but not significantly).

Married fathers have become more involved with children and spend more time in childcare. This includes time in routine care (like bathing or feeding children) and in interactive “fun” activities (like playing games, reading and so on). They also spend significantly more “total time” with children than in the past, as measured by time diaries.

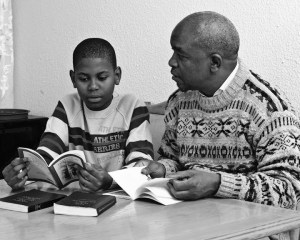

A note on the terminology of “time with” children: When parents’ time is recorded in time diaries, they indicate all activities they have done, sequentially, over a 24-hour day (typically “yesterday”). Researchers often code adult diaries into broad categories of paid work, housework, child care, leisure, and personal care (such as grooming or sleep). The mother pictured here would likely state she was “feeding my child” and this primary activity would be coded as routine child care. If a mother said she was watching television, and at the same time folding laundry, she would be coded as engaged in a primary leisure activity, and a secondary housework activity. She would also be asked –“While you were watching television, who was with you?” She might say “my children” in the case that they were nearby as she watched TV. This latter type of parent-child time is included in “total time” with children in our aggregations.

The idea of “quality time” can mean many different things. Most researchers consider quality time to be certain special activities like talking to, reading with, or playing with kids. Some researchers would consider time with a “warm” parent, who is loving and kind, to be quality. Some might consider parents’ or children’s own definitions about which kinds of time they believe is “quality” time. It may be useful to make a distinction between time in all activities (aggregated to a total or quantity of time with children) versus the subset of time in certain quality activities.

HOW DO QUANTITY & QUALITY TIME RELATE TO CHILD & ADOLESCENT WELL-BEING?

Even as mothers’ time with children has increased from the 1970s, concerns about time seem to have strengthened since mothers of young children marched into the labor force in increasing numbers from the 1960s through the 1990s (Bianchi 2000; Bianchi, Robinson & Milkie 2006). Some refer to the current era as a time of “intensive mothering” (Hays 1996) in which mothers are expected to individually devote enormous amounts of time and energy to ensure children ‘turn out’ to be happy and successful. A research brief discusses the amounts of maternal time, specific kinds of quality time, and children’s and adolescents’ well-being.

SUBJECTIVE DIMENSIONS IN CULTURAL & SOCIAL CONTEXT: FEELINGS ABOUT TIME

How today’s parents feel about their time with children is quite complex. Particularly among parents working long hours, my research shows how feelings of time deficits with children are quite common (Milkie et al. 2004; 2010) and that these have implications for work-family balance and for mental health (Milkie, Nomaguchi & Schieman 2019; Nomaguchi, Milkie & Bianchi 2005; Milkie et al. 2010). Alleviating work strains through reduced hours and more flexibility would likely reduce parents’ feelings of time deficits with their children, and increase parental well-being.

The cultural context of parenting — of intensive mothering and involved fathering, create a bind for many parents. In an individualistic society, with few supports from the state, there are high expectations that parents, particularly mothers, will produce successful, happy children on their own. We conceptualize mothers’ vigilant work to ensure children’s place in the social and economic hierarchy as “Status Safeguarding” (Milkie & Warner 2014). Mothers are at risk of being blamed as “overinvolved” in children’s lives, but they are responding to problems that are larger social and cultural issues (globalization; job markets and instability; vast wealth inequalities).

Culturally, mothers can be pitted as underinvolved — not seeming to spend enough time with children — typically due to employment — or overinvolved (e.g., “helicoptering”) — each denigrating women’s family work and position (see Milkie, Pepin & Denny 2016). Policies to support children (e.g., high quality, subsidized childcare) and parents (e.g., flex-time, paid leaves, paid vacation time, stable schedules) plus cultural shifts in defining societal responsibilities for children’s well-being are needed.